editions

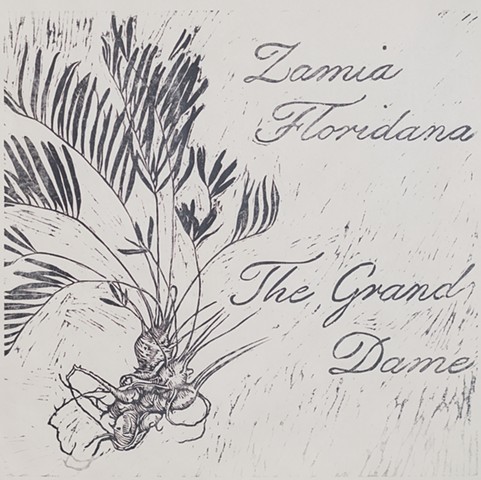

North America’s only native cycad, found in Florida, the Coontie or Zamia Floridana is a “living fossil”, once a dominant form of plant life during the dinosaur age. You may know it now as the host plant for the Atala butterfly, once thought extinct but now experiencing a rare species resurgence thanks to native replanting. But its human history in South Florida is profoundly important: It played a prominent role in the diets of early Native Americans and later, the Seminoles, Miccosukee and early pioneers. This in spite of the fact that, until it is processed, it contains a deadly poison. Well before the arrival of Ponce de Leon to Florida’s shores in 1513, Natives had named the plant (“kunti”) and were pulverizing the starch from its underground root tubers (caudices), then washing away the water-soluble toxin cycasin, to produce flour for breads, cakes and gruels. Later, the Seminoles learned the process, using the plant for years in the Everglades as a primary staple to outlast the U.S. soldiers during the Seminole wars. They called it coonti hateka (“white bread”), and early white settlers often referred to it as Seminole Bread.

The Coontie was a dominant plant of South Florida’s pine rockland, thus when settlers began to arrive it was easy to harvest. An extremely slow growing plant, it had to be harvested from the wild. Almost all early Miami pioneers families like the Munroes and Peacocks maintained small horse drawn coontie mills and could make a barrel or two of starch a week to sell in Key West for $10, by far the most profitable crop at the time. The first water powered mill was on the Miami River as early as the 1840s, and others formed on Little River, Arch Creek and New River in Broward. The starch become known as “Florida arrowroot”, marketed as a healthful flour substitute, especially to children. Large factories were established selling to the National Biscuit Co and to the military in WW1, as it was said to be the first food gassed soldiers could digest. Imagine how much coontie must have existed to handle all that production, and how old and beautiful they would have been. All of which took its toll. In addition to being wiped out along with the rest of the pine rockland (notice the last of the slash pine in photos), in 1925 the FDA banned the term ‘Arrowroot’, favoring industrialized wheat, and the last coontie mill at US1 and SW104th St blew away in the Hurricane of 1926, along with virtually all knowledge of its importance.